The ongoing News International fiasco appears, on the face of it, a good old-fashioned scandal, a “Watergate” for our times, as the #hackgate hashtag suggests. This, the story goes, is a case of a brave investigative journalist bringing hitherto unknown corruption to light in the mainstream media, and, in exposing it, raising questions about the hidden links of the rich and powerful. It’s been a nice return to classic Fleet Street values of speaking truth to power, of exposé and outrage, a pause in the running narrative of the past 10 months- austerity, insurrection and cyberwar. So runs the broadsheet analysis. However, it’s actually an integral part of that thread of confusion and worldwide destabilisation running from Wikileaks, through the Arab Spring, and European and US anti-austerity struggles, to Anonymous and the ongoing Cyberwar (beta).

Whilst traditional commentators are keen to accentuate the differences of these struggles, and paint any attempt to analyse their commonalities as self-valorisation of the most obnoxious kind by western activists, we believe that the causes of these worldwide shifts in power are very much linked. The links lie in our changing attitude to extant authority, to our shared relationship with changing trends in international capital and, importantly, in the role of technology in these changes. The hacking scandal isn’t an event that will lead to a cleaning up of the media and a return to the “values” the NOTW hacks seemingly undermined; rather, it is the spreading of a process of delegitimisation running concurrently across societies worldwide, from the authoritarian regimes of North Africa to the War on Drugs in the US, or the rise of Lulzsec.

The link between the hacking scandal and these new currents of political and social change is based around two new models of crisis; models of the technological freeing up of information, and ensuing deligitimisation of those who have controlled that information. Crisis for them, but for us, a possible opportunity. We call these models “The Napster Moment” and “The Wikileaks Moment”.

The Napster Moment

Faced with slightly changing circumstances, a manager is able to make two choices– to modify how her system operates, or to retain the methodologies of the status quo. The brave or foolhardy manager will opt for change; to optimise the efficiency of their operation. Such a move is inherently risky; if the changes result in reduced efficiency, in failure, then she faces the blame as the manager who implemented the system. Those who want a quiet life will take the sensible option– retain the current model, and invest their energies in plastering over the cracks. With any luck, the system will outlive her tenure, and, if worst comes to worst, she can offer the defence that it was the system that was unsustainable– she just happened to be at the helm when it broke, but it’s the system she inherited and it could have happened to anyone.

This hypothesis on the inherent conservative bias in managerial practice can be applied as a general tendency. Complacency as to the efficacy of any given system tends to prevail amongst those who control the system, whether that system is the music industry, the newspaper industry or liberal capitalist democracy. People keep using the system, people keep abiding by the rules, laws and logic of the system– therefore, people must be invested in the system, must believe in the system, right?

Wrong. Whilst the ideological framework of, and popular consent for, any given system might appear to be largely intact, and ticking over nicely, that’s not in itself evidence that its clients are ideologically invested in that system. The managers continue maintaining the system, unaware of the growing contradictions within it that are threatening to realise themselves at any given point. That point occurs with the Napster Moment- the moment when technology allows the clients to circumvent the authority that manages the system. The moment refers not just to the peer-to-peer music sharing software that allowed users to obtain music free of charge (through piracy), but from the situation the music industry found itself in. For an industry that had, for so long, taken its user’s loyalty and expenditure for granted, suddenly the cat was out of the bag. This is the situation that describes The Napster Moment– a point of no-return, where, due to technological development, a defunct authority no longer has the legitimacy to enforce its hold over its users.

This is more than a technological crisis; it’s an ideological crisis. The ability to pirate music, whether through sharing CDs, taping off the radio or pirating in smaller “silo communities” (non-networked peer-to-peer associations, for example) already existed, but Napster offered a technological and ideological structure to turn peer-to-peer music trading into something which offered a genuine popular opposition to the music industry as distributors.

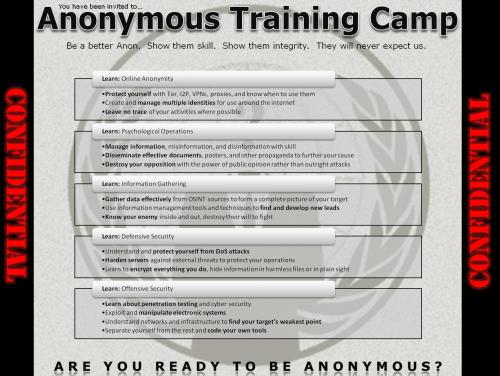

As a model for crisis, we can start to see it in its nascent form across cyberspace. For example Silk Road, an online anonymous marketplace which runs on Tor anonymity software, enables the trading of contraband, especially drugs and controlled substances, for bitcoins, an online crypto-currency, via mail. It’s highly possible that Silk Road, at least as a model, could spell the Napster Moment for the prohibition of drugs in western democracies. Its position here brings us back to our original point about consent: Napster and Silk Road didn’t arise from nowhere to create the ability for piracy and drug-dealing, but rather made it possible to organise those activities in such a way that their networked nature became an coherent challenge to the concept that the intellectual property regime, or the prohibitions on drugs, operate by common consent of citizens. Will law enforcement agencies now be forced to take the line of the music industry and implement increasingly authoritarian measures – seizing personal computers and mail, tapping phones and checking bank accounts, monitoring bitcoin mining – just to maintain the facade of the War on Drugs?

This is the Pandora’s Box of the Napster Moment– an unleashing of the hidden rejection of the dominant ideology committed through mass disobedience from the privacy of your bedroom. In collective anonymity we trust.

The Wikileaks Moment

If the Napster Moment is a tipping-point for mass-networking information which once crossed cannot be retracted, then the Wikileaks Moment is something quite different; a moment within a process where technology allows the release of previously-limited information that totally strips away the ideological justification for a given authority. The scale of the leak is massive– so massive the content becomes almost irrelevant compared with its effect. How many people know the details of the Wikileaks Cables? The real relevance is that the US rhetoric surrounding foreign policy has been revealed as a political disguise for vicious realpolitik, and those who have claimed this to be the case for so many years have had their conspiracy justified.

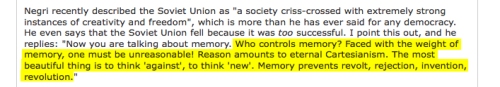

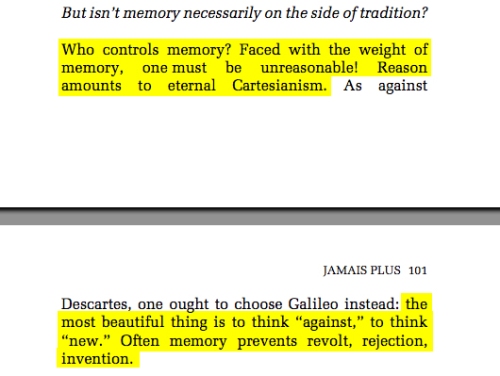

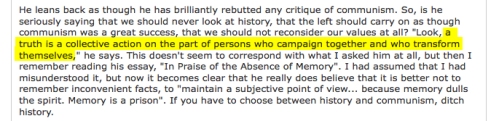

This position was recently brought up by theorist and Gaga-botherer Slavoj Zizek during his recent performance with Julian Assange at the Frontline Club. Addressing the importance of Wikileaks, he said

“So, again, what I want to say is, let me begin with the significance of what you, Amy, started with, these shots. I mean, not shooting, but video shots of those Apache helicopters shooting on. You know why this is important? Because the way ideology functions today, it’s not so much that—let’s not be naive—that people didn’t know about it, but I think the way those in power manipulate it. Yes, we all know dirty things are being done, but you are being informed about this obliquely, in such a way that basically you are able to ignore it.”

What Zizek highlights here is that we all hold an understanding as to the nature of power, but it is due to the sheer quantities of specific data and information that, taken as a whole, undermine our ability to accept previously hidden but acknowledged practices. The “moment” of the Wikileaks Moment is the point at which the traditional tactics of defence and apology– for example, what K-punk calls the “individual as scapegoat-trophy in order to deflect from a structural tendency”– fail because the scale and previously-concealed nature of the accusations have dealt a fatal blow to the integrity and legitimacy of the defendant; or rather, to the complex ideology of commonsense and everyday truth they hide behind.

This is the situation Murdoch finds himself in. The criminal nature of the phone-hacks are less relevant than the proof that News International’s patriotic tears for Our Brave Boys have been crocodile tears, and that the Editorial line of any given paper is a creative fiction aimed at building a saleable identity. The joy of the establishment Left at having their anti-Murdoch conspiracies validated was unrestricted, but missed the realisation that not only did this stripping back of the constructed nature of editorialism apply to “their side” too, but that the rejection of the editorial authority will also be applied wholesale. Wikileaks didn’t damage administrations specifically, it damaged the very legitimacy of parliamentary democracy as a model of just governance. Hackgate won’t damage News International alone, but erode the idea of news outlets as agents of truthfulness or honest political analysis. It was the scale of the leaks, and the incessant feedback of networked commentary in the form of twitter, that pushed this into more than a scandal; and the traditional remedy for a scandal within neoliberalism– the rooting out of bad apples and the independent inquiry– will never restore faith, because nobody wants their faith to be restored.

The wider question that has been passing round militants in the DSG network: Is Murdoch’s “Wikileaks moment” symptomatic of the Establishment’s Napster Moment? The corruption and nepotism of the closed circle of politicians, press and police was a disgusting necessity for the efficient running of the state in the interests of the status quo, but it worked because it was hidden, neatly covered with the facade of the consensus of progressive patriotism, classless society rhetoric and the meritocracy. This conspiracy was a vital tool of governance, but now a precedent of bottom-up transparency has been set, whereby those of us who are excluded from the circles of power have the technological tools (and will) for the constant revelation of such scandals. An endless appetite for transparency, causing an infinite loop of scandal, resulting in a revolving door of administrations. The system of parliamentary democracy and capitalist media as it exists in Britain simply wasn’t designed as a transparent system, and technological developments, hitting at the same time as a restructuring crisis, are forcing open those contradictions. Faced with its Napster Moment, the parliamentary system has two options- either to acknowledge the changing conditions, or, like the music industry, to plough ahead with the current model, and use increasingly repressive and authoritarian tactics to enforce its legitimacy amongst its client base.

DSG EDITORIAL