From the DSG think-tank: a short series of speculative projections for new territories of struggle and focuses for future ideological ruptures. Download the full report here.

Ten Growth Markets for Crisis: A Trend Forecast

I have long believed we do not influence the course of events by persuading people that we are right when we make what they regard as radical proposals. Rather we exert influence by keeping options available when something has to be done at a time of crisis.

Milton Friedman, Two Lucky People

There is … nothing permanent, nor even well entrenched about the current shape of the global economy – still less should it be sacrosanct. It was built aggressively by visionaries who innovated their way into rule-free spaces. It could be radically reshaped by human action, and in the timescale of a decade, not a lifetime.

Paul Mason, Meltdown

In a time of political flux, how do we escape a political discourse which is just a reaction to a series of attacks on our class? How do we place ourselves in a position which is not defensive, but launches a positive vision of social organisation? Where will the challenges and potentials of the coming months and years lie? In Britain mainstream political innovation slumps in the doldrums. Hamstrung by financial and political contingencies, Parliamentary politics offers little in the way of social critique and finds little resonance in the public. But in the field of radical politics? Whilst dissent flourishes, it lingers in the negative, unable to be converted into innovation, by doctrinal discipline or an inability to harness creative thought and speculative conversation. The field lies open for those who wish to write a new story. We have put together a few possibilities to spot these growth markets for crisis; a trend forecast for social struggle.

Let’s outline some key social trends, some growing ideological markets and some possible future scenarios as the class-war continues to warm up. These aren’t predictions, as such – they are attempts to open up our understanding of our current situation as ideologies come crashing down around us. We need to write new stories about how we got here, who we are, and how we’re going to cope with what is to come. Let’s turn tendencies into trends; turn trends into Tendencies.

1 Anti-Usury Campaigns (#usury)

The question isn’t so much ‘will we see a growth in anti-usury campaigns?’, but rather ‘why haven’t they gone mainstream yet?’. A moral and religious response to austerity and financial crisis is something of an inevitability, and we see indications that a renaissance of a historical discourse on the morality of speculation is imminent, from the Church of England to an upsurge in sharia banking.

This attitude, essentially a moral opposition not to capital but to speculation, finds its analogue in the softer and more popular end of the Occupy movement. It could be summarised in the DSG slogan, INSTEAD OF BEING NASTY, CAPITAL SHOULD BE NICE, an anti-structural critique that finds blame for collapse lying not with the system as it is actually constituted, but with a moral failing in the practices of those who oversaw and undertook the financialisation of the economy. Needless to say, as an analysis of power and of the wage- relation anti-usury campaigns would be as much about mitigating opposition to capitalism as it would be offering its own critique. But nonetheless, it seems likely that the first mainstream critique of the financial crisis to gain popular support may well come from the religious sector, with the attendant concerns that history provides us regarding anti-usury rhetoric.

2 Nosterity (#nosterity)

How does a society cope with the trauma of an imposed regime of austerity? Through resistance, but also through reaction. A rising cultural trend is the amalgamation of austerity rhetoric with a strange and toxic form of nostalgia; what might be called ‘nosterity’. An implicit form of social bullying, this runs deeper than phenomena like Keep Calm and Carry On, or endless invoca- tions of a return to the Winter of Discontent. It’s a framing of an economic and social crisis in such a way as to suggest that advocating social reorgan- isation is not just unnecessary but in some way a refusal to play a part in the narrative; that to complain and dissent is equivalent to a moral failing for being unable to endure with stoicism.

In doing so it fills a desire for contextualisation, lacking in the poll-led politics of parliament, with a stringent ahistoric explanation of austerity as part of a national moral fibre. Through the drip-drip of everyday culture, and a fetishisation of the everyday contingencies of our ancestors, we can expect an ever increasing trend of nosterity in everything from fashion and entertainment to childcare policy and employment conditions. In design, we face a return to WWII signifiers; in media coverage of dissent, a hip, retro take on everyday issues of class struggle filtered through the rose-tinted spectacles of ́68 and Jarrow, or grim portents of ‘bodies left unburied’. This is about more than comparisons; it’s about removing the manifestations of struggles from their causes in everyday inequalities and injustices. Nosterity is social policing via the medium of kitchenware.

3 Social Democracy as the New Utopia (#labourutopians)

It’s a conversation we first referred to when talking about student demands during last year’s Tuition Fees protests, but it’s worth expanding into all aspects of a mainstream political conversation which focus on what is left of the social partnership built between labour and capital in the post-war years.

Put simply, whilst we oppose attacks on the welfare state as an attack on our class, a return to social-democratic social models is simply unfeasible – not for economic reasons (although such an argument holds considerable weight) but for socio-political reasons. What built and sustained the welfare state was a model of social-democratic political organisation which simply does not exist anymore. A large part of its dismemberment was undertaken by the neoliberal market reforms after 1979, but we have yet to accept that it was also being eroded by demands coming from within the working-class – demands of social liberalisation, increased personal autonomy and a rejection of the fetishisation of work, or indeed work itself – which traditional structures of class organisation could not deliver without breaking up their own bureaucratic structures.

Can we really expect a return to the glory-days of the social partnership through a series of rearguard actions? No – social-democracy can only be built through a progressive vision of a certain form of (limited) social transformation, and in reality that unformulated vision today is the new utopianism of the British political imagination. To rework that oft-quoted maxim of late capitalism – ‘It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism- but it is easier to imagine the end of capitalism than the restoration of social democracy’.

4 Hey! Let’s not go to work today! (#internstrikenow)

Unpaid internships are becoming a steadfast part of our new economy, taking newly graduated workers in precarious employment and forcing them to give free labour in exchange for that ‘extra-something’ that will secure them a foothold in a competitive labour market. Organising around precarious workers is an indisputably difficult task: the law favours employers, traditional labour unions have, by and large, washed their hands of such workers and companies are adept at economically and emotionally exploiting such staff with fast turnover.

How might an organisation based around the economic power of unpaid interns work? We propose focusing on the strengths of interns, and suggest a strike for social reproduction; that is, not just withdrawing ones labour but creating new models in the process. A 6 month intern strike, where young strikers liaise via social media to start producing alternative political media, organisations and campaigns? Following the model of autonomy centres and the punk movement they helped nurture across Europe, the #internstrikenow could utilise the time and network-creativity of strike-interns to produce the infrastructure for a creative movement built in opposition to capital. After leaving the boring free-labour of the office internship and spending time guiding and creating your own cultural and social movement, why would you want to return? #internstrikenow – making autonomy work for you.

5 Currency Zones of the future (#CZF)

Financial industries engage in a race to the bottom as currency markets see the late growth of their long tail, with diversification into multiple niche marketplaces. With the gradual reallocation of wealth across new and old frontiers, currency projects that 6 months ago were strictly the reserve of the early adopting techno-utopians and anarcho-libertarians find a new uptake on the part of the early Mainstream money markets.

The needs of the marketplace and society at large acting to retain the status quo of wealth distribution, through the adoption of an even spread approach to financial security. This isn’t about innovation, it’s about consolidation; money markets defending their position, much as, post-Lehman, banks legislated and lobbied their way into defending their right to unsustainable capital ratios.

We’re likely to see the rapid take-up of digital currencies, LETS, time banking and formalised blackmarkets, as overlapping zones of exchange work to form an ecosystem for the complex stratification of capital. On top of this, with the power of organised labour much restricted by new anti-union laws, we can expect to see employers establishing new currency zones within their work-forces – for example, food stamps and payments-in-kind. Early utopianism in alternative currencies face adoption into a new model of the company store. In the future, supermarket employees will be at least partially paid in loyalty card points.

6 Rent crisis (#rentcrisis)

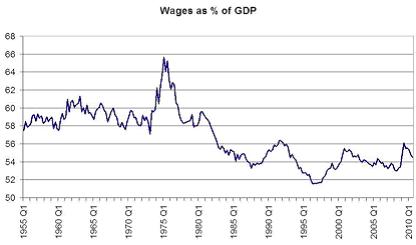

House ownership has long been a key principle of Conservative governments, both in order to build a credit economy in order to weaken organised labour, and as part of a long-term campaign to ‘make Britain conservative’. This policy, buoyed by growing economic inequality during the last Labour government, lead to a rise in buy-to-let mortgages. With sustaining these huge mortgages becoming a key focus of the government, and avoiding the politically-catastrophic drift into negative equity, Britain, and London in particular, faces a rent crisis. This is a crisis whereby frozen wages and rising rents combine to suck out increasing chunks of the take-home wage of low- paid, precarious and key workers, and it is a recipe for social tension. Out of rent-crisis are born rent-resisters.

Rent-resistance is a complex and difficult form of direct action to organise, but we predict it will show its first roots amongst student populations. Student housing in the form of university halls of residence offers a perfect breeding ground for a campaign that relies upon social solidarity; not because of the make-up of students as individuals, but due to the close, social living quarters, the relative lack of something to lose and the fact that all students in a hall of residence share the same landlord. Will 2012 bring a reinvigoration of the student movement of 2010, focusing not on fees but on the increasing, hidden squeeze working-class youth are facing, through a series of rent-strikes? Will we see new working-class youth identities formed on the back of student rent-strikes?

7 Britain’s Bread Riots (#breadriots)

Amongst the factors behind the Arab Spring (collapsing EU export market, high graduate unemployment etc) a key flash-point, particularly amongst the urban poor, was that of rising food prices. Despite the collapse of the commodity trading bubble, taken up by hedge-funds moving out of structured finance markets after the financial sector collapse of late 2008, the CFPI (Commodity Food Prices Index) continues to run high. Whilst DSG normally reject a ‘blame-the-bankers’ approach to financial and social crisis, this is one sector where speculation on commodity markets directly takes food off the plates of the world’s poorest people. There are, of course, other causal factors for a rising CFPI; the question is how long is it politically sustainable?

With wages falling in real-terms across the large British public sector, and unemployment rising against a similarly rising CPI, the issue of food poverty is once again pressing at the doors of many across Britain. This isn’t simply an issue for those out of work, living on increasingly punitive benefit and workfare regimes, but also for those in-work; with the collapse of the social partnership the idea that a wage should be able to cover the essentials of life is disappearing.

Long-established controls on social stability are being withdrawn. The safety-net of the welfare state is slowly being replaced with free-labour schemes for corporations and violently anti-worker legislation condemning millions to breadline misery. Social solidarity increasingly lacks mechanisms of enhancing social cohesion. How long till we see riots at the delivery and supply depots of Britain’s supermarket giants?

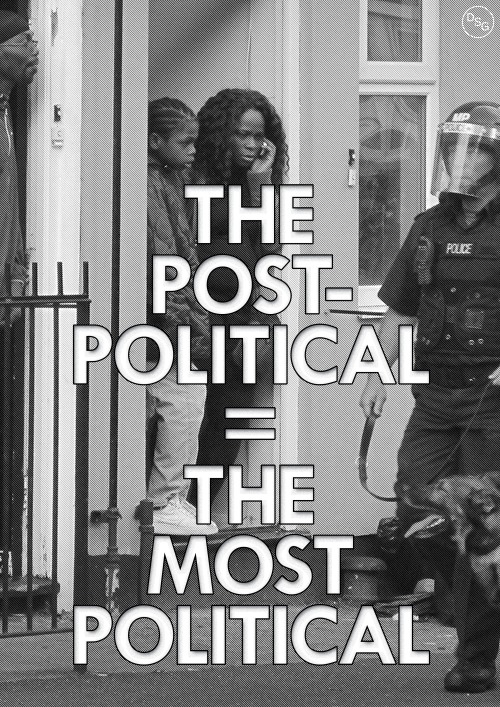

8 Crisis 2012: The Olympian State (#crisis2012)

The Olympic Village will be an island within London; an island of peace in a discordant London, an island of late-Capitalist prosperity in an ocean of austerity. It will be an island, and an island at all costs. A post-democratic logic is settling over government policy, whereby the greater good of national pride is being used to justify ‘special-measures’ against protest and dissent, in much the same way as we saw over the period of the Royal Wedding. This is the ‘new normal’, from the militarisation of London and attempt to present protest as inherently criminal (as witnessed by the use of large-scale containment barriers on a recent trade union demonstration), to the growth of ‘temporary’ policing facilities on previously common land and the restriction of protest placards, allowing ‘enforcement officers’ to enter private homes to destroy or conceal such placards.

The Olympics has become a showcase endeavour to demonstrate the unity and power of the national State, with the subtext that whilst we may be suffering under austerity, England endures.

The extreme special-measures the state will take to restrict any embarr- assment in the form of anti-government protest will linger well past the end of the Games. The Olympic legacy for London will be felt on the shoulders of working-class people for years to come, in the form of an increased perceived legitimacy for stop-and-search powers, anti-dissent laws and further empowerment to the state apparatus.

9 Autoreductionism (#proletarianshopping)

Fuel poverty is reaching epidemic proportions. The RPI is rising at incredible speed, whilst large sectors of society face pay freezes (real-term pay cuts). Families are forced to choose between essential items for their children. Why not go shopping as a community?

Autoreduction is the collective determination of commodity prices enforced by community solidarity. It is not a symbolic protest against the high cost of living endured by working-class people, but a direct action aimed at relieving that burden. We see a dynamic social movement emerging, using decentralised models of organisation (such as UK Uncut) to produce replicable structures for autoreduction across the UK. Large groups of people arriving at their commuter station in the morning, forcing themselves through the turnstile; an organised troop of families fitting out their kids with winter coats, then demanding to see the manager for negotiations; a national campaign of underpayment on gas and electricity bills; in all instances normal people saying ‘we will pay what we can afford for the essentials of our life’– paying the ‘political price’ for goods and services. Why shouldn’t collective demand become a significant factor in establishing value?; if supermarkets can fix a cartel of suppliers, why can’t working class people fix a cartel of consumers? Why go shopping when you can go proletarian shopping?